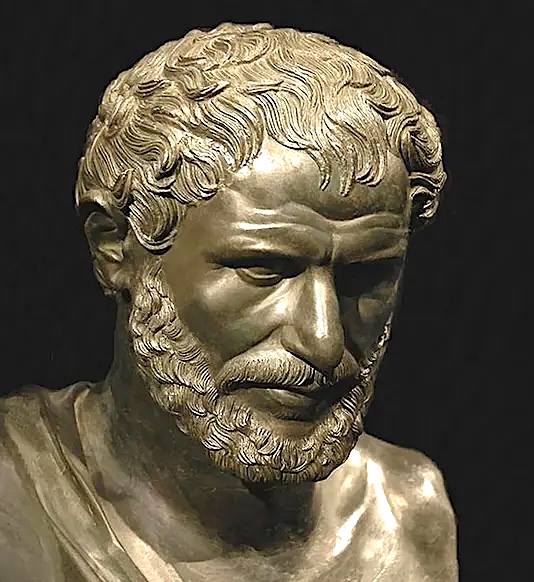

“You cannot step into the same river twice (ῷ αὐτῷ ποταμῷ οὐκ ἔστιν ἐμβῆναι)” – Heraclitus

Today’s word — to heraclitize, heraclitizing, viz., to follow or espouse the opinion(s) of Heraclitus.

The concept of ‘heraclitizing’ originates from the Metaphysics of Aristotle: “For it was from this view that the most extreme of the opinions mentioned above blossomed forth; that is, the opinion held by those who are said to heraclitize (ἡρακλειτίζειν)” (Meta. 1010α11)

Thomas Aquinas also this notes in his Commentary on Aristotle’s Metaphysics: “And this is the one which he called heraclitizing, i.e., following the opinion of Heraclitus…who claimed that all things are in motion and consequently that nothing is definitely true.” (In IV Meta., lec. 12., 362)

The context for this criticism originates from Aristotle’s discussion and defense of the principle of non-contradiction (in the above text), viz., that, “the same attribute cannot both belong and not belong to the same subject at the same time and in the same respect”. (1005b20-21) For example, you cannot both be sitting in a chair and not sitting in a chair at the same time and in the same way.

Heraclitus and others (Empedocles, Democritus, Parmenides, Anaxagoras) seem, however, to have cast doubt on this principle due to their views about the nature of reality. In a word, they were naturalists (to use a modern term) who considered reality to be entirely made-up of physical bodies (matter, energy, etc.).

Physical bodies are in constant motion. They subsist in a state of persistent change – generation, destruction, growth, decay, and so on. Even today we recognize this fact. All particles are made up of energy, and energy implies motion.

Heraclitus and other naturalists also held that knowledge and sensation are identical. What we sense we know, and what we know we sense. But perception is in a constant state of flux. It follows that knowledge must also be in a constant state of flux. During the day we perceive, e.g., a white flower. At night, the flower is black (not white). So what color is the flower? To the senses, it is both. To say then that “the flower is white” and “the flower is not white” are thus both true statements. It follows that contradictory statements are both true, which overturns the principle of non-contradiction.

But this result is only the beginning of the problem. If the flower is both white and is not white, then the flower is also neither white nor not white. Hence, if both statements are true, then both statements must also be false (since if P is true, then ~P is false, and if ~P is true, then P is false). It follows that everything is both true and false so that nothing can be known with certainty, if at all.

It is this latter view and consequence which Aristotle (as well as Aquinas) addresses in the above remark. He states that it is precisely their metaphysical views that lead to such absurdities. If reality is reducible to a constant state of flux, then indeed nothing can be known with certainty. But reality is not (or need not be) such. Although physical things are in a state of flux, they are nonetheless in flux from and toward more fixed states in being, both potential (coming-to-be, ceasing-to-be) and actual (being this and that). At one moment, matter is in a fixed state that we recognize as a tree, and in another, as a bird, or a human being.

These latter states, or actualities, Aristotle explains, are the result (as their cause) of form (eidos). In contrast to matter, which is material, form is not material. More specifically, it is ontologically other-than-matter (since not material and im-material both imply negation; but form is not just the negation of matter, but is a positive real cause of being, distinct from matter).

With the addition of form the absurd problems that the materialists face vanishes. For we may now say that during the day the flower is in a state of actuality that includes the form of being a flower and the accident of being white. It also includes potencies that exemplify other accidents, such as being grey, black, and so on. Furthermore, whether white or not white the flower remains a flower (due to its form). Hence, although the flower can be both white and not white, it cannot simultaneously be both white and not white in the same way, at the same time, in the same respect, and so on. It follows that the principle of non-contradiction is upheld and certain knowledge is possible. For we may say with certainty that the flower is white during the day and black (not white) at night, and both statements are true, since the statements express different conditions for the same flower, but not the same condition simultaneously.

In the end, to “heraclitize” means to engross oneself in the above absurdities and contradictions as the naturalists, and so to deny all possibility for knowledge. Indeed, such heraclitizing became so severe among the ancient thinkers that it was said that the philosopher Cratylus, in dismay of saying anything true, simply remained silent and used his finger to indicate whatever he meant, since doing so was faster than speaking, and he might catch hold of truth, as it were, before it fled away.

In recent times, heraclitizing has once again taken hold of philosophy, along with naturalism, and various philosophies that seek to deny the principle of non-contradiction (e.g., dialetheism). Like Aristotle, we ought to do our best to oppose such views since they inevitably have the result of leading thought into skepticism, confusion, and like Cratylus, into dumb silence.

So if it is said (following Heraclitus) that you cannot step into the same river twice, then we ought to raise the question of in what way the river is meant, viz., the water that is now passing, the river in the sense of the entire water and its bank, and so on. Analysis will easily reveal that given the right interpretation you can in fact step into the same river twice, and in another sense, you cannot. In either case, contradictories statements are never found to be simultaneously true, and knowledge is upheld.

I end this post with something of a joke on Cratylus:

Heraclitus: You cannot step into the same river twice.

Cratylus: You cannot step into the same river once.

Aristotle: You’re speaking Cratylus.

Cratylus: Oh, right!

He starts pointing around.

Leave a comment