As I grow older, I find myself increasingly inclined toward the Platonic position that the body is something akin to a prison of the soul. My body is my own, yes. And yet, I and my body are not one and the same thing.

In youth, we experience a false sense of security in the body. We feel boundless, invincible. The body is like a companion who travels the world with us. Youthful ambitions stretch out into the world. The young man or woman desires material success—and rightly so—for with it comes financial security, a family, earthly enjoyments.

Then, suddenly, out of nowhere, sickness or some other calamity strikes us. Or we awaken to find that thirty years have passed, and our body is older, weaker, breaking down. Once a source of vitality, the body becomes a source of pain and suffering, a burden that we are forced to carry around.

From this, a new desire emerges: To be rid of the body.

This should not be mistaken with suicide. Suicidal desires stem from a state of hopeless despair. For sure there is a likeness. But the desire to be “rid of the body” may also originate out of a sober recognition of the transitory nature of physical life, from which the desire to find a more firm existential ground to stand on arises.

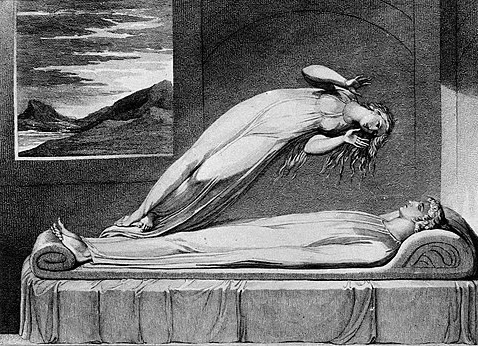

Suffering, sickness, the slow decay of the body—under the right conditions—can produce a therapeutic desire to be separate from the body. In suffering, the soul is compelled to reach out beyond the body in search of spiritual consolation. This can of course be refused. Insofar as it is not, the desire becomes a form of spiritual transcendence.

The desire for transcendence issues from a principle that proclaims itself to be something more than the body. In suffering, the contrast between the body and the soul sharpens: The body is a source of suffering. The body is a cause of pain. Would that I might be rid of this burden!

Out of this purifying fire the soul—like the Phoenix—rises and turns its gaze beyond suffering, beyond the body, beyond death, in search of something more.

We see people today chasing after immortality. They experiment on themselves, inject new and untested medicines, and imagine that their consciousness might one day be uploaded into a digital machine. They identify themselves with the body—and as a result, who they are and what they are becomes increasingly obscure to them.

All things desire to live. This desire is instinctual, and it is satisfied by the simple fact of being alive in the here and now. Beyond that, animals have no concept of continued existence. Apes and chimpanzees do not make New Year’s resolutions. Only the human being seeks to live beyond the now.

In suffering, this desire is intensified. The soul longs to live on—but not in this mortal coil. As a prisoner, it seeks to escape from the flesh, to live on beyond the death of the body.

Yet suffering is not the only path to this separation. Plato reminds us, again and again, that the true purpose of philosophy is to prepare the soul for death. By this he meant that the student of philosophy ought to be instructed to turn the gaze of the soul toward what is eternal—the deathless forms, the Good itself.

In doing so, the soul comes to recognize itself as like unto such things.

Leave a comment