I often find myself struggling to make decisions: what to do, what to write, what path to pursue. But what is involved in any act of deciding?

I raise this question for the reason that making decisions has become increasingly more significant to philosophy today. The more uncertain we become, the more uncertainty becomes a part of the philosophical process, the more the problem of making a decision takes the forefront of all issues. Furthermore, according to the situation that characterizes philosophy today, making a decision has become almost a necessity. Philosophers can no longer risk indecision—not while the scientist and everyone else busies about. It is better to be busy with something, one might say, than to appear to do nothing. For the philosopher today this means: busy about truth, whether in fact or only in appearance.

The thing about deciding is its utility. Even when one is lost—on a highway or in the woods—one can still make the decision to go this way or that. In such cases, deciding becomes a precondition for getting anywhere. Without a decision, we remain in a state of uncertainty, hovering between possibilities. And there is nothing more unproductive than the failure to make a decision. So-called “decision paralysis” can be absolutely soul-crushing. Days, weeks, years may pass while we consider this or that option. Before we know it, we are older versions of ourselves. And still we are in the same place we started—uncertain and undecided.

To make a decision, philosophically, means to decide on the issue of truth. What is truth? Can the truth be known? Which truths? How? Insofar as truth is not apprehended, to make a decision means to will that some proposition be true, as if to say: ‘I decide that P is true,’ despite not seeing that this is the case. This is the problem of decision.

As it stands, we must take a very serious look at the issue of making a decision so as to understand its role in determining the course of philosophical inquiry.

Making a decision is a psychological and even a spiritual act, since core questions often demand more than just reason or argument. They often require an examination of conscience, as it were, of the soul of the philosopher. For after all, the issue is one truth, and therefore, of the motivations behind the decisions made in regards to truth, especially when the truth is not seen.

Everyone is so busy today. When we are not working, we are busy with our cell phones and other instruments of distraction. Society likewise chastises those who are not busy enough. With minor exceptions, the not-busy-enough are seen as idle, using the goods of society without providing any benefit, and in the end, becoming a burden upon society. And no one wants to appear to be a burden, let alone actually be one.

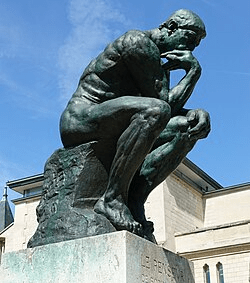

At the same time, we seldom pause to sit down, to take a step back from it all, and to reflect upon what led to the decisions that led to all this feverish activity in the first place.

Obviously, for most people there is little time in an otherwise busy day to take the time to basically do nothing—as if thought counted as real work! There is always the risk that by taking too much time to reflect, we might end up in a more unfortunate state of uncertainty and, consequently, more indecisive. And certainly no one wants this.

But for philosophers—or at least those who call themselves such (including those both in and beyond the academy)—not taking the time to do nothing, to reflect on the motivations behind one’s decisions about truth, would be, one might say, intellectually dishonest.

For if the philosopher is too busy, then who will take the time to reflect on the reasons and motivations behind why we are all so busy? Bees go about their day, busying about. But human beings are not bees. We build nests, yes—but we can also consider why we build them.

This is not a call to society to support a select few to go about their day doing nothing. God forbid anyone should have so much time on their hands when the rest of society has so little. Philosophers are not nobles and lords to sit in lavished castles while everyone else labors around them. The philosopher too must also labor.

And yet the labor of philosophy is not like other things. In a way, the ‘busy philosopher’ is a contradiction in terms. For again, who will do the real reflection on life, death, and all the rest—which is to say, on the truth of existence and human existence—if the philosopher is too busy to do so? And by this I mean: taking the risk of real, authentic thinking, which is tantamount, ironically, to the risk of not deciding, and therefore doing nothing, and potentially becoming nothing. For after all, real reflection carries such risks.

So, in a way, the labor of philosophy is to take the risk of doing nothing, and consequently of accomplishing nothing, contributing nothing to the benefit of society, and ultimately becoming a burden. The very utterance of such things is anathema.

But such a risk the philosopher must take, that is, if one would undertake to truly do philosophy. For the doing of philosophy requires that we first un-busy ourselves, sit down, and reflect in silence.

One might compare this situation to that of a gold panner. The gold panner leaves home, even country, treks out to barren lands, and spends his or her days in the weary labor of sifting through rocks in search of gold. The gold panner labors, and yet, unless gold is found, their labor comes to nothing.

In like fashion, the philosopher must depart from the goings-on of everyday life, reach out in silence in search for answers to the fundamental questions of reality and human existence, spend his or her time sifting through ideas, until truth is found. And if truth is not found, then like the gold panner, their labor comes to nothing.

Of course, the potential reward is that one might stumble upon gold, which is to say, upon truth. And what a discovery this would be!

But such a discovery, let it be clear, does not come about by making a decision. The thinker cannot create gold by an act of will. It comes about rather by taking the time to do nothing—reflecting in silence, sifting through the rubble, watching and waiting, risking becoming nothing—until the light of truth, like gold flickering in the sun, is revealed.

Note: This essay has a subtle context. An alternative title could have been, ‘Contra Badiou’. I quote: “My entire discourse originates in an axiomatic decision…” (Alain Badiou, Being and Event, I.2, p. 31)

Leave a comment